Living Standards and Plague in London, 1560–1665

Joint with Morgan Kelly and Cormac Ó Gráda

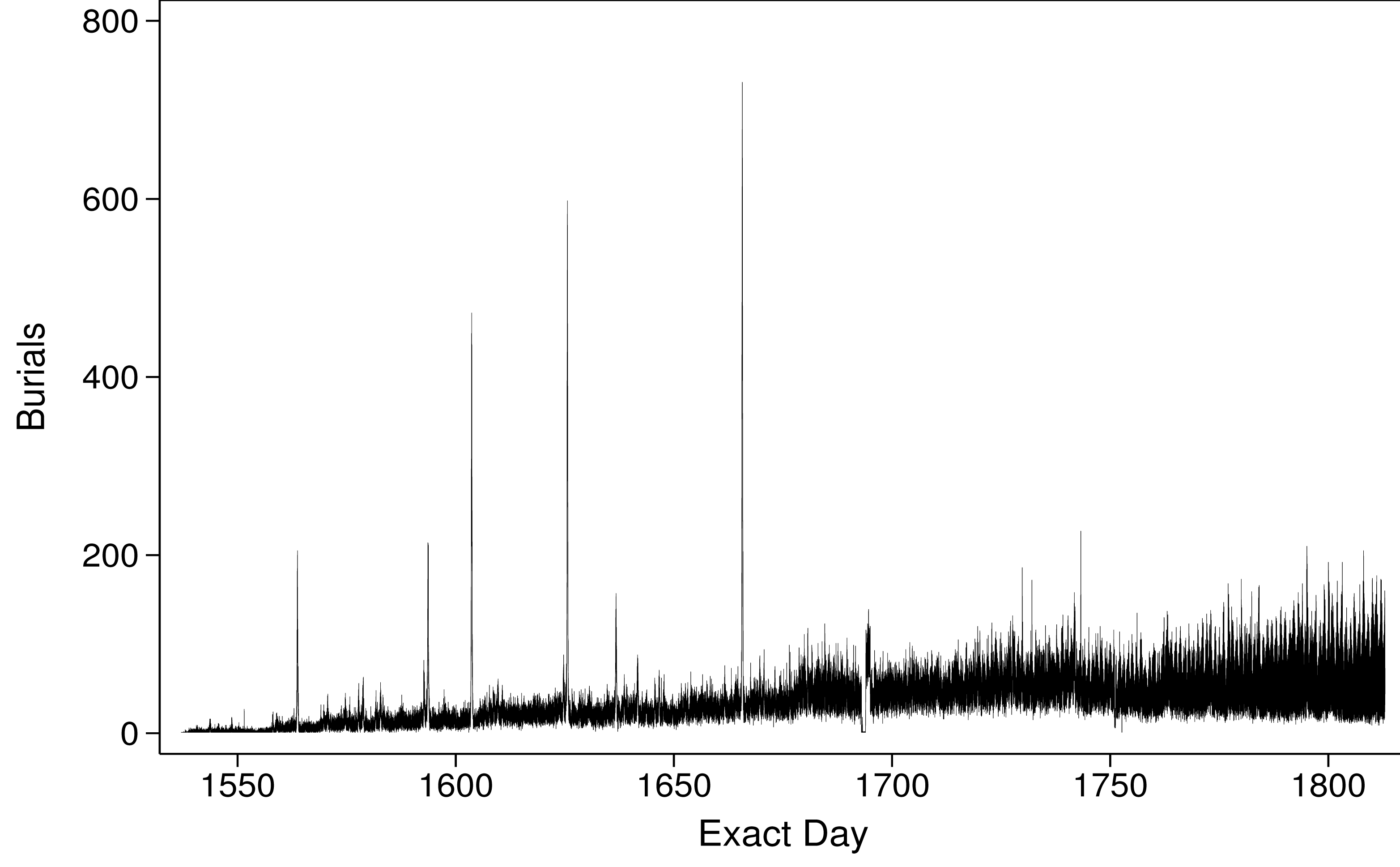

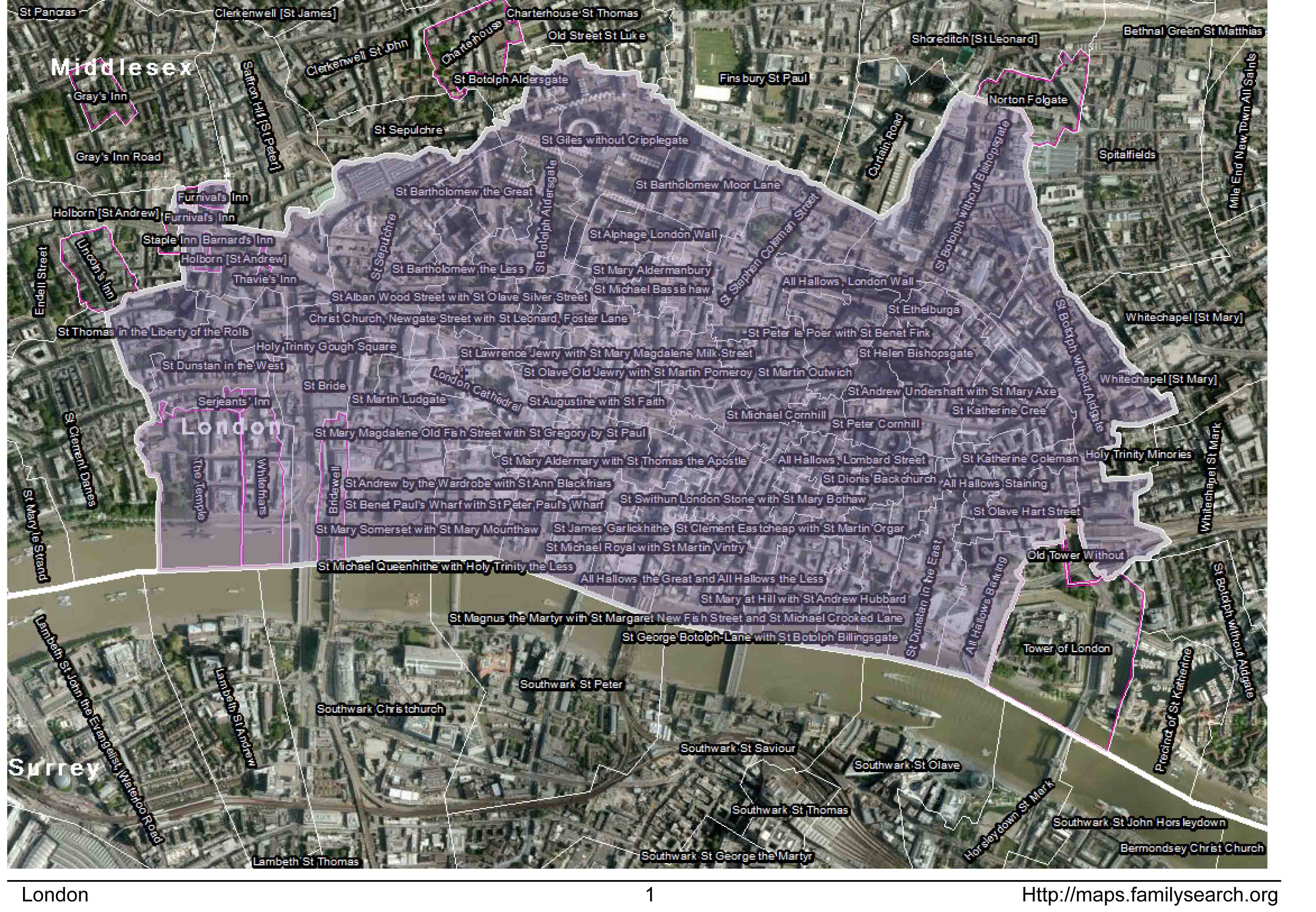

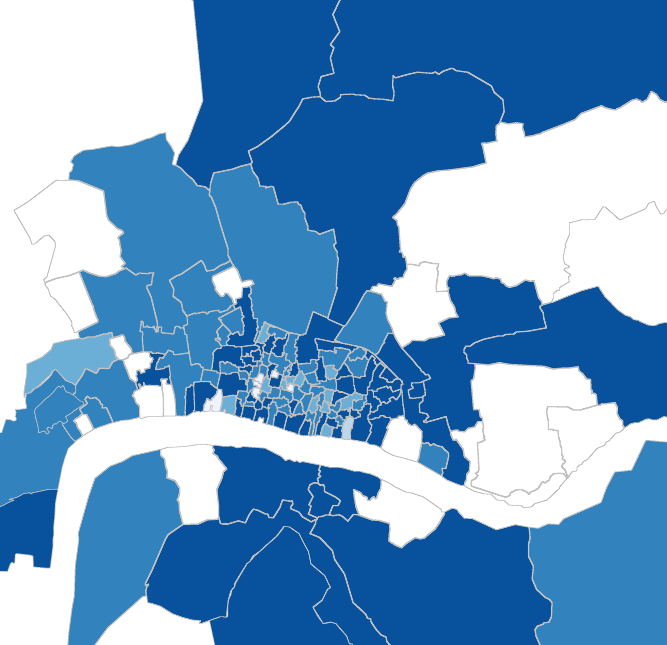

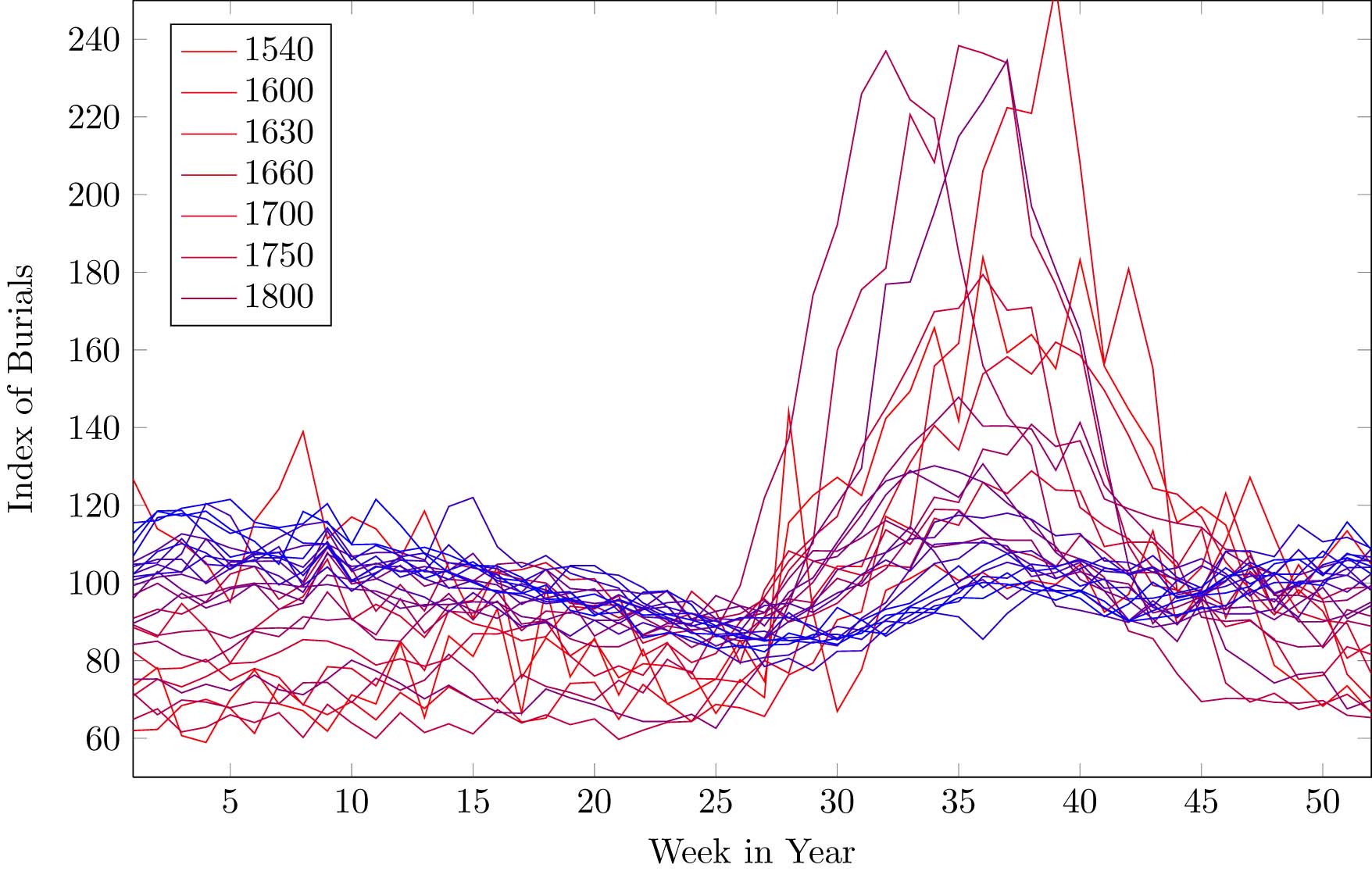

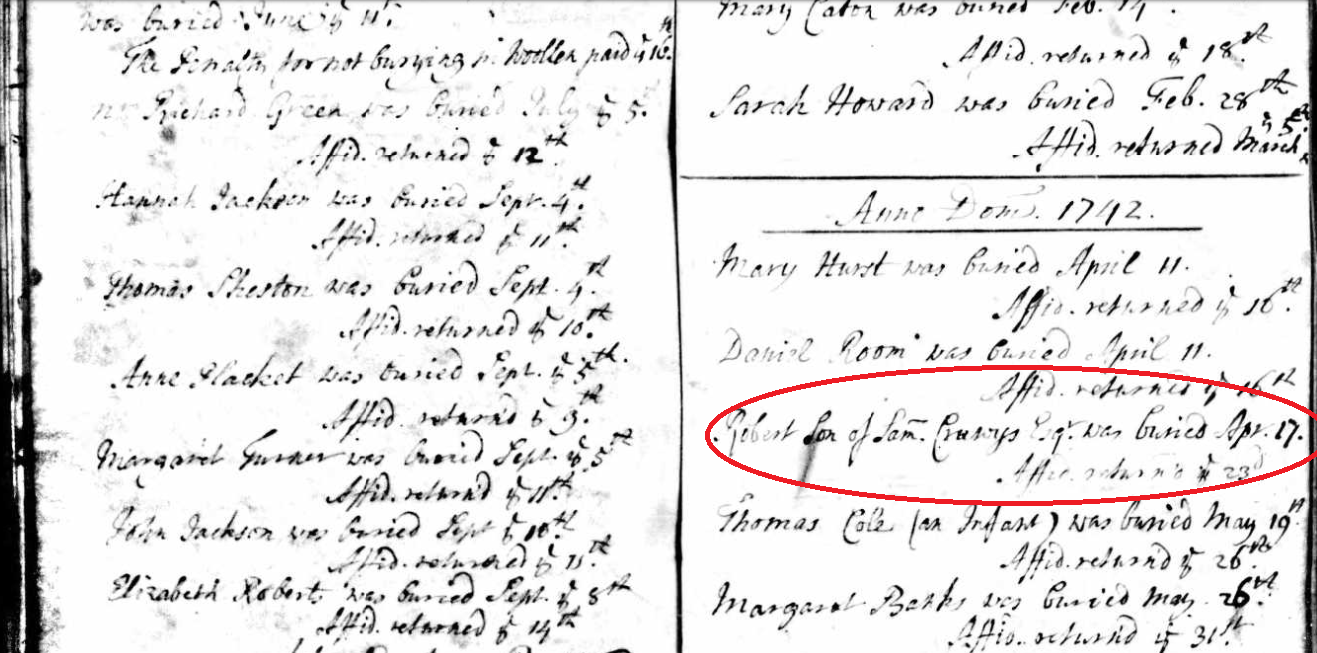

We use records of 870,000 burials and 610,000 baptisms to reconstruct the spatial and temporal patterns of birth and death in London from 1560 to 1665, a period dominated by outbreaks of plague. The plagues of 1563, 1603, 1625, and 1665 appear of roughly equal magnitude, with deaths running at five to six times their usual rate, but the impact on wealthier central parishes falls markedly through time. Tracking the weekly spread of plague before 1665 we find a consistent pattern of elevated mortality spreading from the same two poor northern suburbs. Looking at the seasonal pattern of mortality, we find that the characteristic autumn spike associated with plague continued in central parishes until the early 1700s, and in the poorer surrounding parishes until around 1730. Given that the symptoms of plague and typhus are frequently indistinguishable, claims that plague suddenly vanished from London after 1665 should be treated with caution. In contrast to the conventional view of London as an undifferentiated demographic sink we find that natural increase improved as smaller plagues disappeared after the 1580s, and that wealthier central parishes in the early seventeenth century showed positive natural increase outside plague years whereas the poorer suburbs showed substantial deficits and a strong positive check.